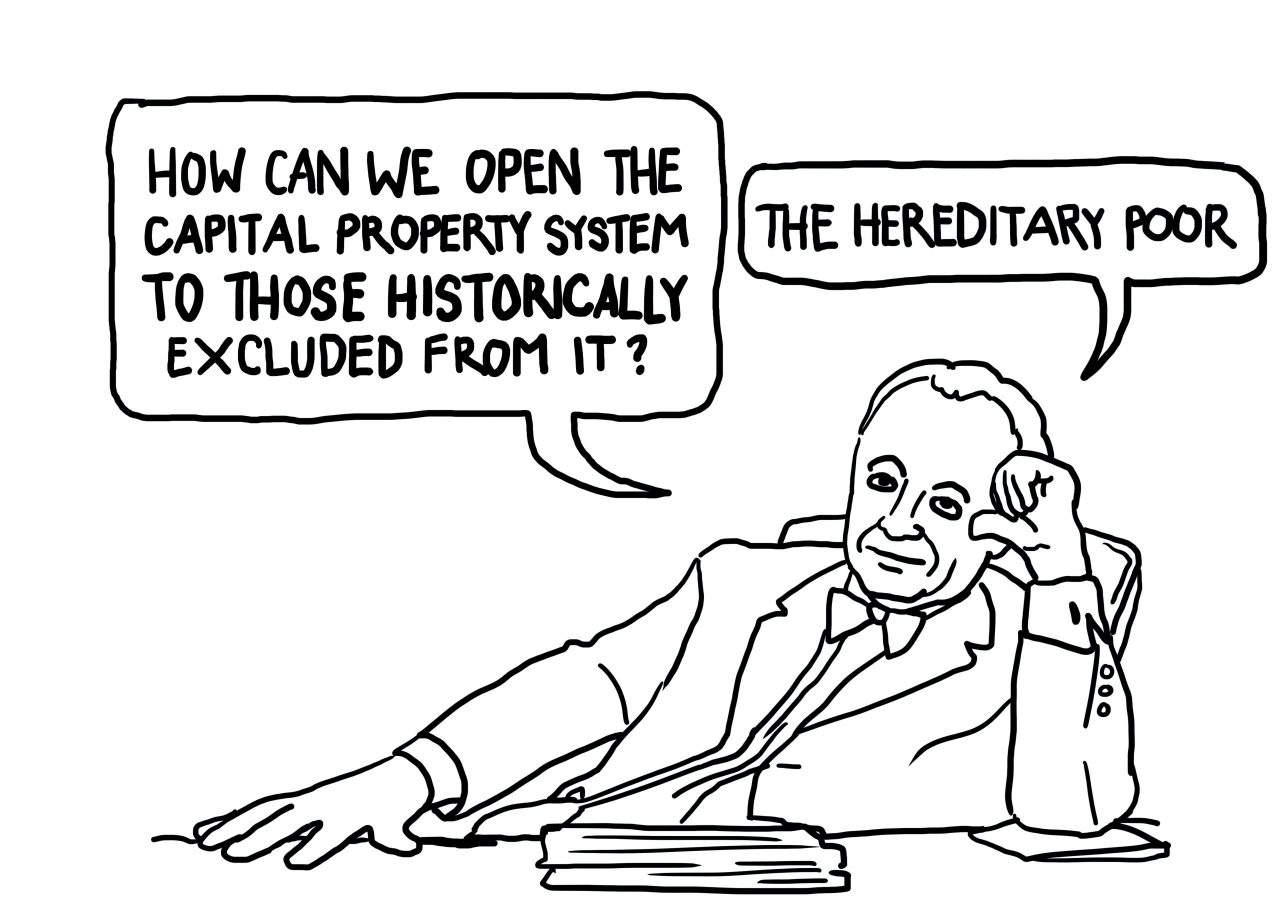

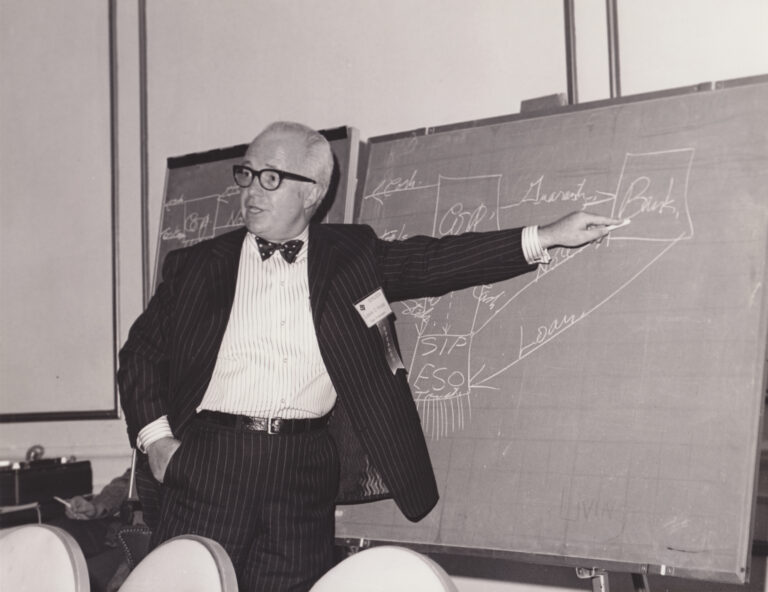

Louis O. Kelso (1913-1991) believed in the promethean power of people. He wrote “The Capitalist Manifesto” even though he did not like the title chosen by the editor. Kelso’s ideas and especially their implementation even today offer solutions for current societal problems. In 1956 he enabled the employees of the closely-held newspaper chain Peninsula Newspapers, Inc., of Palo Alto, California to buy out its retiring owners through a new financing concept: He created the “Employee Stock Ownership Plan” (ESOP). Thanks to this financing technique working people without or with little savings are enabled to buy stock in their employer company and pay for it out of its future dividend yield. The ESOP was thus the prototype of the leveraged buy-out which was embraced enthusiastically by the later emerging private equity funds (KKR, Blackstone, etc. who Kelso knew all personally) – even though aiming at different objectives.

Kelso implemented the first CSOP in 1958 in Fresno, California. The CSOP is related to Kelso’s best-known financial innovation, the employee stock ownership plan (ESOP), that enabled millions of American workers to become (co-)owners of their employer companies. Both plans repay the acquisition loan not from wages or savings but from the future earnings of the shares acquired.

Local farmers – the main consumers of fertilizer – utilized the CSOP to organize a new corporate entity for the production of anhydrous ammonia, Valley Nitrogen Producers Inc. (Kelso Institute, 1976). Several large petro-chemical companies, who also set prices, controlled the fertilizer market at that time. Carl Haas, the founding president of Valley Nitrogen Producers, later explained that he took this initiative because the oil companies had been raising the price of anhydrous ammonia to a level – 250 USD per ton –, which he considered exorbitant. He took the problem to business and corporate lawyer, Louis Kelso. Upon learning that Haas himself had no capital to invest, Kelso invented the CSOP and then persuaded the farmers of the Central Valley to become consumer-shareholders of this radically new kind of company. As a result, the long monopoly, which the big petro–firms had maintained over the fertilizer industry in the Central Valley was broken with the fertilizer price dropping from USD 250 to USD 66 per ton.

Although not a regulated public utility, Valley Nitrogen Producers Inc. had a utility’s main characteristics. Central Valley farmers, as long-term consumers of fertilizer, were bound to their suppliers exactly as consumers of electricity, gas or water are bound to the suppliers of these necessities. As the need is constant, the relationship is secured by mutual dependency. The proposed corporation also met Kelso’s other criteria for a CSOP (Kelso Institute, 1976):

the investments subscriptions were proportional to long-term needs for the product;

the shares’ subscription were acceptable to the bank;

limited corporate income tax;

investors contractually committed to buying fertilizer for the maximum period permitted by anti-trust laws, in this case, seven years; and

the earnings of capital to be paid out fully and regularly to shareholders after debt amortization and operational costs.

Since the corporation, under tax regulations then in force, qualified as a farmer-cooperative, income and dividends were tax-exempt, making the loan even more feasible. Nevertheless, when Kelso applied to the major banks for financing the first CSOP, initially asking for USD 20 million with an additional later installment of USD 100 million, to his amazement, the banks one after the other refused to make the loans. Finally Kelso persuaded the Berkeley Bank of Cooperatives, a cooperative bank, to finance Valley Nitrogen Producers as a co-operative even though it was not conventionally structured.

The CSOP made 4,580 farmers instant shareholders of the new fertilizer manufacturer, Valley Nitrogen Producers, Inc., an investment of USD 120 million (which inflation adjusted would equal today about EUR 915 million). Each farmer subscribed to buy the percentage of shares proportional to his fertilizer needs over a period of seven to ten years. He himself made no financial contribution. The CSOP was mainly secured by the bank loan from the Berkley Bank of Cooperatives, which was backed in turn by the farmers’ stock subscriptions. In the management board’s report on the project nine years after its founding, a sample calculation for a typical shareholder was as follows (Valley Nitrogen Producers Inc., 1969):

He subscribed shares valued at USD 19,095 and agreed that the dividend yield of these shares would be used to repay the Berkeley Bank of Cooperatives loans over a period of ten years.

In turn he was entitled to USD 30,271 dividends during the first nine years of the plan.

Of these dividends USD 21,131 were paid out, of which USD 16,398 was used to pay down his subscription obligation with a remaining balance of USD 2,697 for the last year of the plan.

The difference between the dividends serving the principal and total payments, that is, USD 4,733 was the farmer’s interest payments for the loan financing the acquisition of his stock.

Additionally, the farmer received the remaining portion of his dividends, that is, USD 9,139 in the form of credits representing loans granted to the company during the last three years.

This credit was used for the company’s growth and geographical expansion. By 1978 Valley Nitrogen Producers Inc. had already four production facilities in California and one in Arizona, as well as a network of distributors in these two states (Stockton’s Port Soundings, 1978).

The price of the top-selling fertilizer dropped from USD 250 to USD 66 per ton (Kelso Institute, 1976).

Even with this drastic price reduction, Valley Nitrogen Producers Inc. quickly became debt-free and profitable.

Since the corporation, under tax regulations then in force, qualified as a farmer-cooperative, income and dividends were tax-exempt, making the loan even more feasible. Nevertheless, when Kelso applied to the major banks for financing the first CSOP, initially asking for USD 20 million with an additional later installment of USD 100 million, to his amazement, the banks one after the other refused to make the loans. Finally Kelso persuaded the Berkeley Bank of Cooperatives, a cooperative bank, to finance Valley Nitrogen Producers as a co-operative even though it was not conventionally structured.

The Valley Nitrogen CSOP not only created significant assets for 4,580 farmer-shareholders, but according to estimates of the Kelso Institute, it also saved California farmers more than one billion dollars in fertilizer costs over a 15-year period, when fertilizer prices began to rise worldwide. The first CSOP was a great success – for the company, for its farmer-consumer shareholders and for consumers in general – despite the fact that conditions were less than optimal. Unlike a utility, the company had to operate on an unregulated market.

Today Kelso’s best-known financing technique, the Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP), is an integral part of corporate America. At the end of 2016 there were 6,717 ESOP and 2,898 ESOP-like plans in the USA, with about 14 million employees participating, that is 13 per cent of private sector employees holding around USD 1.3 trillion in assets (NCEO, n.d). The overwhelming majority of ESOPs are found in unlisted private companies (firms whose shares are not traded on public stock exchanges); in about 4,500 companies, employees are majority owners and in about 3,500, the ESOP holds 100 per cent of the employer company’s shares (ESOP Association, n.d.). However, the Valley Nitrogen CSOP remained the only practical example of a classical CSOP implemented by Kelso.

Address:

Kelso Institute Europe

Kreuzbergstraße 76

10965 Berlin

Phone:

+49 (30) 62 86 01 06

E-Mail:

contact(at)kelso-institute-europe.de

Benchmarking Employee Participation in Profits and Enterprise Results in the European Union, the United Kingdom and the United States